“Every day we were coming in, and people were asking me, ‘Is today the day that we stop coming in?’” Eric Camp remembered. By the end of March of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had swiftly occupied every corner of our lives, halted our day-to-day routines, and placed us under lockdown. Despite the calamity, education in the chemistry department at the University of Washington (UW) trudged forward, overcoming obstacle after obstacle, thanks in large part to behind-the-scenes work done by the Undergraduate Services team.

There are several scientific instructional technicians on the team who engage in a variety of tasks such as running the department stockroom, coordinating the labs for courses, or ensuring student safety during experiments. Their work is critical to the success of the lab courses during each quarter. At present, Eric Camp heads the Undergraduate Services team as its director.

Camp is no stranger at UW. He arrived at the UW first as a student. Later, he became a scientific instructional technician (tech), eventually taking on the role of director after several years as a tech. Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic posed a significant challenge for Camp and his team, so they sprang into action, conjuring up solutions to keep undergraduate education afloat.

Eric Camp during a lab demonstration (2016).

First, the team had to figure out how to safely work in the lab while maintaining distance. “We designated all the technicians as essential employees. We put them in a hybrid position where they would be remote for three days and come in for two days. We set up their schedules so that there was a technician in [on] every single day,” said Camp.

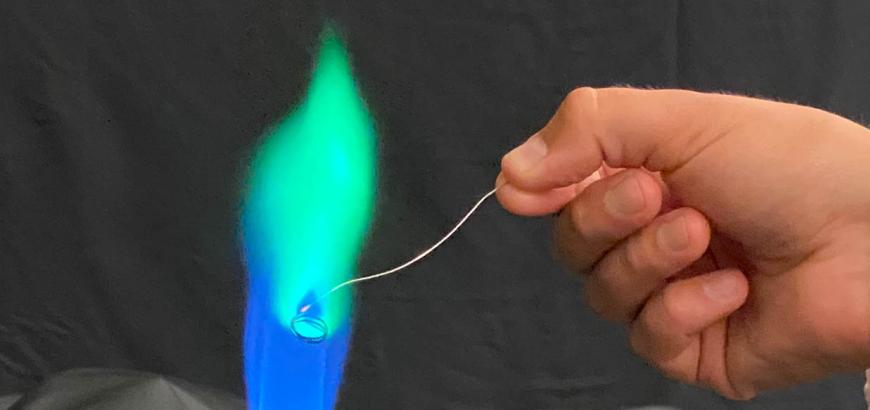

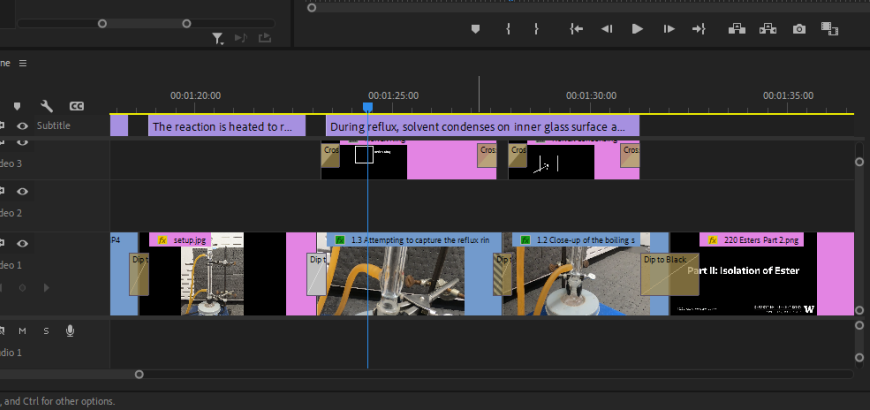

To move the lab courses online, the team decided to create videos of the experiments and PowerPoint presentations to accompany them. One of the techs, Leesa Kurtz, had previous experience working as a freelance photographer shooting weddings and high school senior portraits. Her experience staging scenes and using image and video editing software became an invaluable asset as a result.

Leesa Kurtz, Scientific Instructional Technician on the Undergraduate Services Team.

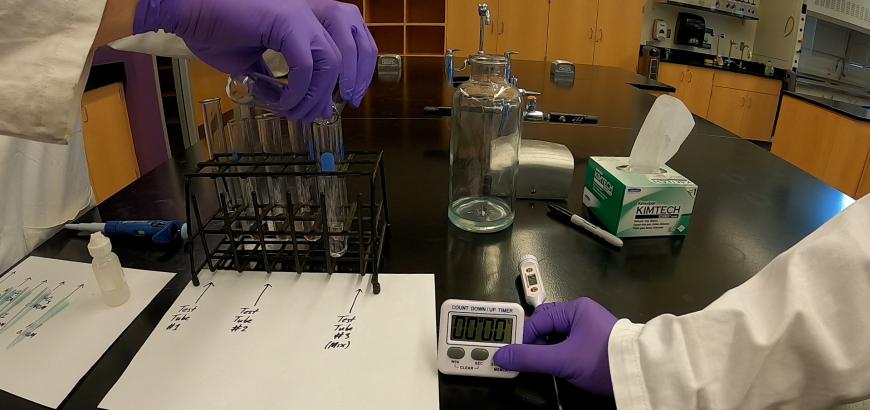

“The timeline that I was on when I was churning out videos during the fall quarter was insane. I was putting out two to three videos a week, plus photo editing for each course at the same time,” said Kurtz. Fortunately, the video-making process was a shared effort. Associate Teaching Professor Andrea Carroll shot most of the video Kurtz edited, and several techs and teaching assistants (TAs) stood in as actors to perform the experiments. Kurtz focused primarily on editing the videos for the general chemistry labs, but she also aided another tech, Kayla Milano, with making the videos for the organic chemistry labs. In addition to the videos, Milano stepped up to fill several roles during the pandemic.

“We lost our other organic tech to bigger and better things; he got a job elsewhere. We also lost our stockroom supervisor [who started veterinary school], so Kayla was running the stockroom and the organic labs at the same time, [while] also making videos for the organic labs,” said Camp. Despite the heavy workload, Milano emphasized her effort to aid the TAs, “We just tried to help everyone survive . . . I always tried to make sure [to say], ‘You can come to me for help, or even if it’s just [to] release frustrations about the situation,” said Milano.

Kayla Milano, scientific instructional technician on the Undergraduate Services Team.

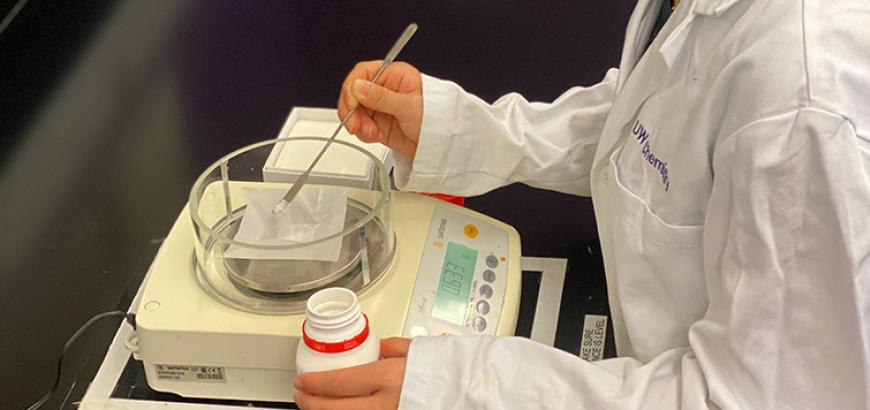

While many of the techs were racing against time to virtualize the lab courses, providing support for each other along the way, a few were also undertaking an endeavor to conserve some form of in-person experimentation for students. Brandon Bol and Ed Grant, techs for the upper divisional chemistry courses, assembled lab kits with four or five, ready-to-run experiments for several courses, one example being Quantitative Analysis (CHEM 321).

“My partner tech, Ed Grant, had tasks each quarter producing these kits [and] modifying them . . . He was the first one to work with Dan [Fu] to produce [the kits],” said Bol. At the onset of the pandemic, Assistant Professor Dan Fu adapted experiments for CHEM 321 to be used in the kits, Grant did most of the kit assembly and shipping to students, and Bol acquired and prepared chemicals necessary for each experiment included in the kit.

“One of the things we built for the kits was a 3D-printed spectrophotometer.” Bol said, “[We] build the casing, and then we buy all the parts so we can build a pretty good, homemade spectrophotometer.” After a student receives the kit, they work through assembling the device before running an experiment with it. Camp commented on the educational value for students, and said, “Most chemistry now is kind of a black box where you put your data in and it spits out an answer. In this case, they’re actually doing the hard work of making a spectrophotometer and running an experiment. They have a deeper understanding of how it works. We’re all really proud of that.”

Scientific Instructional Technician Brandon Bol adjusts lighting for a photo shoot in an undergraduate teaching lab to create content for remote instructional material.

The kits for CHEM 321 went through several adjustments, optimizing them for student use. They evolved further when Associate Professor Matt Bush taught the course later on during the pandemic. “Matt’s doing a lot with paper chemistry devices . . . For instance, if you’re in a poor country, you don’t have access to a cutting-edge laboratory,” Bol said, “It shows cheap and innovative ways to look at problems and still do analytical and quantitative chemistry.” For student’s in CHEM 321, one experiment they ran involved performing a titration directly on a paper chemistry device.

However, the implementation of the experimental kits didn’t come without their own challenges. In order to ensure equity for students in the course, the kits were designed so that everything needed for the experiment was included in each kit. “We want to set up an experiment where we have to assume the student has no resources. We can’t just say use the vinegar that you have in your home. What if they don’t have that vinegar? What if they don’t have a microwave? What if they don’t have a house? We need to create these kits so that they can be used without anything else,” said Camp.

Additionally, shipping brought even more problems to navigate. The small bottle of household vinegar available on Amazon could not be shipped to each student because it was only available to Amazon Fresh subscribers. Furthermore, the vinegar would have needed to be shipped separately to avoid reactions with other components of the kits. Despite the efforts of the team, “Amazon was like, ‘Nope, we’re not doing that.’ We actually got Amazon to say no to shipping,” Camp laughed.

Prof. Andrea Carroll fills an electrochemical half-cell for the Electrochemistry lab in CHEM 162.

Amid the numerous challenges that the pandemic brought upon the UW and student learning, there’s a silver lining. The successes of the Undergraduate Services team over the past year have helped to reimagine how lab courses are run, even for in-person learning. The assembly of the 3D-printed spectrophotometer will likely become a consistent experiment in the line-up for Chem 321. Furthermore, the videos created for the general chemistry labs can be provided to students in the future as study lectures, and the organic chemistry videos will likely be repurposed to run organic chemistry as a flipped-lecture style course.

The efforts of the Undergraduate services team were critical to running lab courses this past year. For most of it, they worked non-stop. “In general, the life of an instructional technician is cyclical. You have incredibly busy times and dead periods. And techs tend to use those dead periods to predict what’s going to happen in the future and lessen those busy times,” said Camp. Now that the pandemic is in retreat, the members of the team will receive a well-deserved dead period after an unpredictable, and almost perpetual period of business.

Story by Gunnar Goetz

Gunnar Goetz is a graduate student in the research group of Prof. Sarah Keller where he studies the morphology of phase-separated membranes. Following his experience as a writer for his high school newspaper, Gunnar is pursuing freelance science writing as a possible career after finishing his Ph.D.